Sometimes I get asked, how I managed to remember so much text during my career as an actress. The simple answer I tend to give is, that I did not remember the text. People get stunned. What I mean to say, is that plays are never purely text to me and I don't remember them as such. I rather remember a whole sequence of where to move when, which emotions occur, things you are trying to do with your partners and how the character develops during the play.

Already with the first encounter with a text, which is typically the moment when the whole crew gets together and reads a text out loud, is a moment where you start looking for the things that speak to you, for emotions the text evokes, for images concerning the environment. After that, you typically need time to memorize text, some actors more than others. Next, you would rehearse with the text. You would put the pieces together with your partner(s) in space and time to tell the story. I have found that without rehearsing, I would loose the memorized text after two days. But once you are in the process of rehearsing you are starting to craft the line of development through space and time of a given play. And it is the whole performance that my memory was able to pull up pretty easily for months to years.

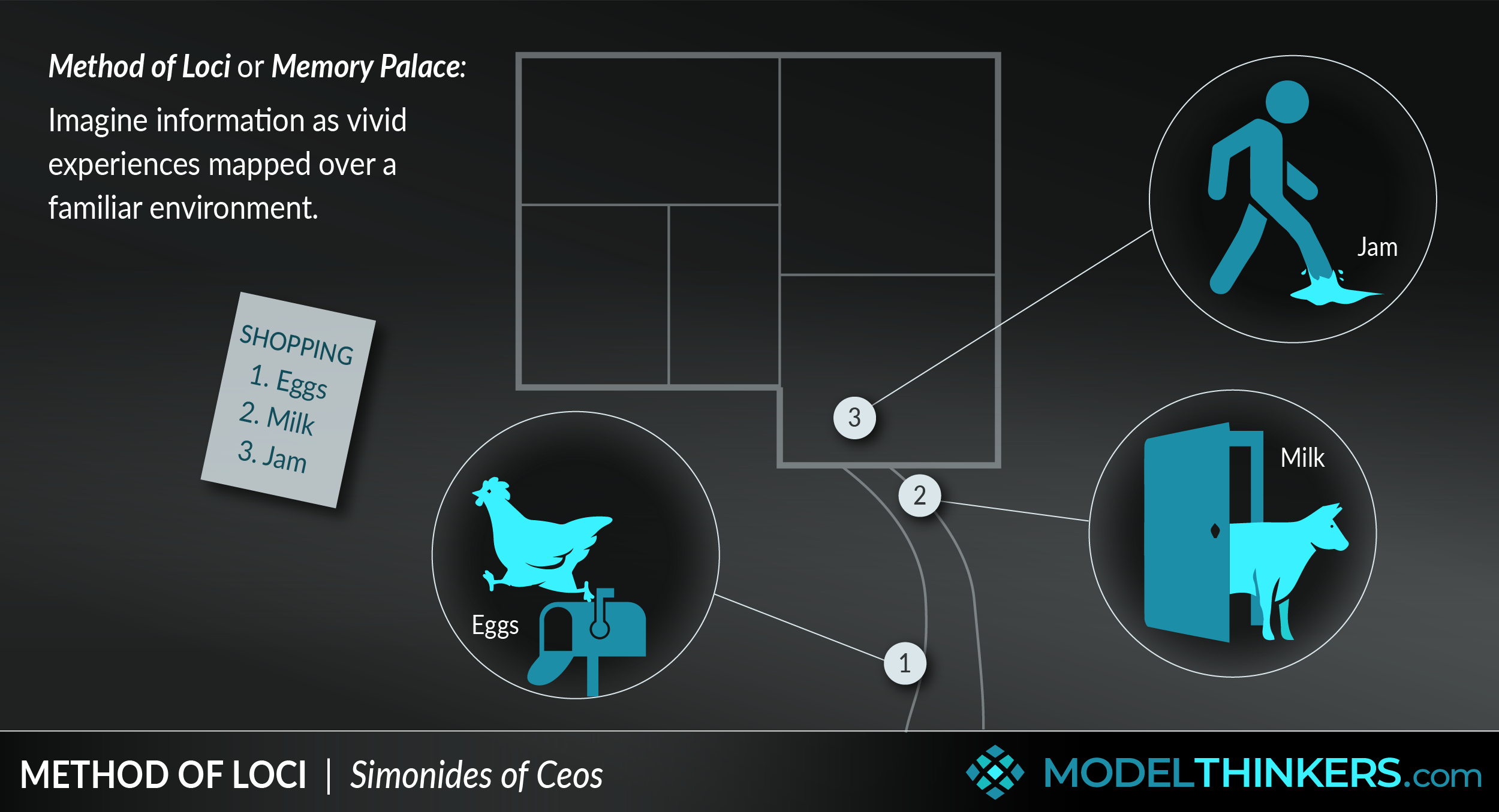

How can you use this for a life outside of theatre? To the left is the link to a podcast and a graphic on the side that I found insightful. And here are some tips on learning and memorizing out of my own experience:

1) Use timing: Don't expect yourself to remember text. Help your brain with creating a network of logical sequences instead. After A comes B, after B follows C, and then, surprisingly, F is happening, which transforms A. Not everything you are learning may follow the line of a narration, but as our brains love structures of narrations, this can help you in other domains, too.

2) Use imagination: Try to see a picture in your mind of what you are reading about. Reading slowly will help your mind to develop such a picture.

3) Use space: Using gestures to memorize what you are learning can be helpful, as if you were talking to yourself. Also, dedicating a certain places in your surroundings to prompt you to remember things you wanted to learn.

4) Use your voice: Reading silently only involves the eyes. Reading out loud already adds your listening sense to the visual input

5) Think of application: As you are going through the learning process try to think of situations that your current learning may help you with. Make it as specific as possible - who will be there, how may they react, how is that different to what you have done before. It is important that you can see some benefit in your learning. Otherwise, it will be just too much brain effort without rewards, so not likely that you can pursue it for long.

6) Use your emotions: Emotions are markers to remember something. Any emotion can be a marker, if it is disbelief, joy or the famous aha-moment. The important part is to realize what you are feeling. Sometimes you can reconstruct a situation by remembering a feeling and then re-constructing what caused the feeling.

7) Use play: You can use two pens to have a dialogue about the subject you are trying to remember. Or you can use your kitchen equipment to map out a full process. Any analogy or similarity between your subject of learning and the things you already know, will help you with remembering what you wanted to learn.

8) Accept failure: Regardless of all the techniques that you are able to apply, there may be days when nothing seems to work. Remember that learning is not a linear process where you brain will retain the same amount of information every day. Stay away from blaming yourself. Try again next time.

9) Practice. Don't expect any learning to stick with you if you don't repeat it, put it into your own words or apply it.

I hope you feel a little curious about your personal learning. Some of these tips may feel like stating the obvious to you, others may be a little awkward. I encourage you to experiment and maybe even come up with your own tips.